2019: Humanity’s race against itself deepens (2): fascism or revolution?

The article below has been written for publication in the first issue of a new online journal, Советское Возрождение (Sovetskoe Vozrozhdenie- Soviet Renaissance)to be produced in Russia. This journal has now been published and posted on RedMed as well as in Russia (click here). The article was originally penned in English and was translated into Russian. This is Part 2 of the original English. Part 1 was posted on RedMed earlier (click here)

We are racing against ourselves, oh beloved,

Either we will take life to dead stars or death will descend on our planet.

Nazim Hikmet

The rise and rise of proto-fascism and reaction

2019 has also been a year in which the earlier tendency toward the rise of fascism in disguise and of other types of reactionary political movements has continued. These two trends have to be carefully distinguished since the dynamics behind them and their class nature are totally divergent.

Let us first take up the rise of fascism in disguise. That there is a whole family of political parties especially in Europe that base their politics on racism and offer the working masses a way out of the crisis by laying the blame on immigration and “foreigners” is no secret to anyone. These are parties that divert the attention of the working class away from the scourges of capitalism and point their finger at foreign workers, migrants and refugees, Islam and, of course, Jews. The term “populism”, adopted by all bourgeois commentators and unfortunately widely used on the left as well, is a gross misnomer. These are fascist parties in all respects except for one: they do not yet have armed militia that are meant to spread terror in the rest of the population, to break the resistance of the organised working class, and pose as a rival to the armed forces of the countries in question. That is why we insist on calling them proto-fascist movements. (Some, such as the Greek and Ukrainian organisations, as well as the Nordic Resistance movement, do have their militia. Jobbik in Hungary was another example until, strangely enough, it took the initiative of disbanding them. The long standing Turkish fascist party MHP, an ally of Erdoğan’s AKP, also has its “sleeping militia”, so to speak.)

2019 saw new victories for this current in world politics. The European elections once again confirmed this rising trend. Marine Le Pen, with her newly named party Rassemblement National (National Rally) replacing the time-worn Front National, swept past Macron’s party to come in first in the European elections. So did Salvini in Italy with his Lega, after a coalition experience during which he displayed all his demagogic skills to win over the poor and destitute of the country by laying the whole blame for their plight on immigrant workers. In Germany, the Alternative für Deutschland came in third in the same elections. This was an affront and a warning as it came on the heels of the Chemnitz and Köthen events of fall 2018, when pure blooded fascists staged mass riots and were accommodated by the local organisations of this party. This was a lesson in action showing the world what proto-fascism is: at any given moment in the development of the contradictions of a country or an entire region, the cocoon that has been prepared by these movements may be filled with unmistakably real fascist content. This is the dialectical relationship between proto-fascism and fully-fledged fascism.

The place of people like Trump and Boris Johnson on the political spectrum is obviously more debatable. However, it is our conviction that Trump personally displays clear signs of affinity to fascism. This was displayed by his stance on the white supremacist and neo-Nazi rally of Charlottesville, Virginia in the summer of 2017, when he condoned the existence of these groups as legitimate. The same goes for Boris Johnson, who proved in his brief term as prime minister before the December elections that he has no time for the niceties of parliamentary democracy by proroguing parliament for five weeks at a time of vital decisions for British society. That his attempt at gagging parliament was frustrated and that he suffered defeat after defeat is only a sign that shows that British society is not yet ready for such fascistic practice. We underline “not yet”, for his resounding victory at the polls after all that he did in his short term in office is a signal that shows the real direction in which British society is moving.

What is indisputably common between Trump and Boris Johnson, on the one hand, and the Le Pens, the Salvinis, and the Farages of the proto-fascist movement, on the other, is that both partake of a new tendency within the ranks of the international bourgeoisie, in particular of the imperialist countries, a tendency that poses an alternative to the rampant globalism of the last three decades. There is a holistic logic behind Trump’s trade wars and the Brexit of Boris Johnson: in both cases, a section, a growing one, of the bourgeoisie of the country in question opts for a solution, more nationalistic in nature, of saving its own economy rather than continuing on the road of saving capitalism in its entirety, which, after the 2008 debacle, has proven to be a cul de sac. It is this logic that lay at the basis of Hitler’s and Mussolini’s economic policy and it is this logic that shows the way forward to the Le Pens and the Salvinis (whether this will play out at the level of each country or of the EU as a whole is now a debate within the proto-fascist movement of the EU). Without being aware of this new “solution” to the crisis of capitalism that has arisen within the bosom of the international bourgeoisie, very little can be understood about world politics today. The impeachment procedure against Trump is, first and foremost, a struggle between the globalist and nationalistic wings of the imperialist US bourgeoisie.

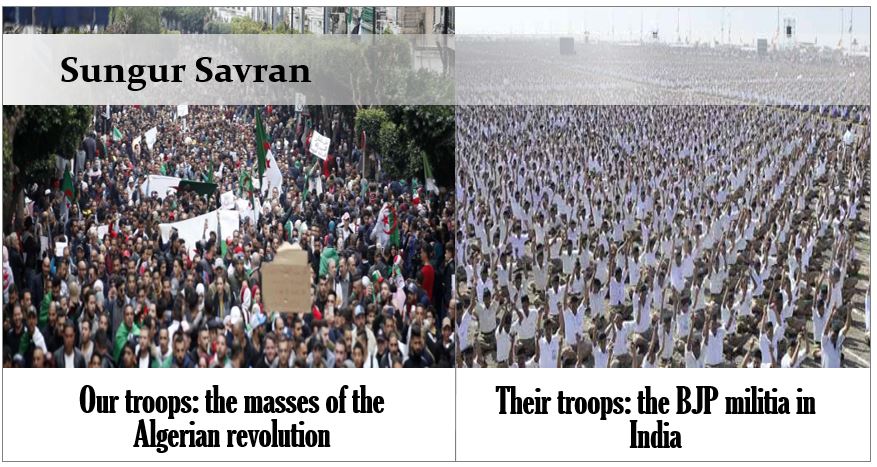

Of proto-fascism one can speak also in the cases of countries such as Brazil and India. The two cases contrast in one very important aspect: in Brazil a politician, Jair Bolsonaro, almost the entire international left has dubbed “fascist” possesses no serious political formation that can form the basis of a rise of fascism, while in India the nature of a party that has a clear racist Hindutva ideology and wields well-established militia forces, in other words a party that stands very close to fascism in every sense if it were not for the fact that India is no imperialist country, is hidden from view by a politician who keeps winning elections and is treated as a respectable interlocutor by his international counterparts. Or was. With the new citizenship law and the population register that have been put into effect, 2019 will probably go down in Indian history as the year when Modi brought down his mask to reveal his Hindutva fascism.

There are still other reactionary forces around the world that are either on the rise or trying to recover their strength and to regain lost positions. These are cut from an entirely different cloth relative to fascism. Such is the wide variety of Islamist movements that have marked this beginning of the 21st century. One falling star is Erdoğan of Turkey. Although he has recovered from his strategic defeat at the hands of the Gezi people’s rebellion of 2013, he has lost a countless number of allies since then, being led to run after new allies each time and ending up in the arms of the traditional fascist party of Turkey, the higher echelons of the army, the earlier personnel of the famous deep state (a concept bequeathed to the world literature of political science by the Turkish experience, a dubious honour) and wings of the Turkish mafia. He is no longer able to rule alone, having lost at least one fifth of his electoral support. And yet he still clings to his ideology of Rabiism, that of ruling over the Sunni Muslim world of the Middle East and North Africa, even trying to bring parts of sub-Saharan Africa and the Horn of Africa under his sway. A clear sign of this insatiable drive for hegemony was his invasion of northern Syria east of the Euphrates river this fall, in addition to pockets that he had already taken under his control west of the same river. The ostensible reason is to push the Kurdish militia, which Turkey considers terrorists, away from the Turkish-Syrian border and resettlement of new groups in that region. But the subliminal message is clearly control over parts of Syrian territory for future purposes of expansion or negotiation. After Syria, the Erdoğan government has now set its eyes on Libya, taking the side of one of the self-declared governments of this divided country, signing an Exclusive Economic Zone memorandum of understanding with it, and promising it military assistance in the current ongoing war in that country.

If Erdoğan clings to his idea of ruling over the Sunni Muslim world through the agency of the Muslim Brotherhood network, he is at least still the president of a country with a powerful military. The more radical Islamists of Al Qaeda and ISIS (Daesh) are climbing back after defeats suffered and after their charismatic leaders, respectively Osama bin Laden and Bakr al Baghdadi, were assassinated at the hands of American forces. There is no sense in labelling these and similar organisations “Islamic fascism”, as there is almost nothing in common between them and fascism used in any intelligent sense except their shared penchant towards resorting to unlimited violence. These organisations are the product of a confluence of factors, into which we need not go, of which the humiliation of the peoples of the Islamic world, both in the lands where Muslims live, in particular in Palestine, and in the depressed cités of metropolitan Europe is the decisive one. This means that the questions of Euro-centric racism and imperialism, on the one hand, and Islamic terroristic organisations, on the other, are symbiotically tied to each other and that the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region and Europe form a single metabolism that feeds both racism and terrorist attacks. That the Islamic movement keeps gaining ground in different parts of Africa as well (the Horn of Africa and the Sahel countries) and that they can be kept under control with great difficulty (but not be defeated) only with the assistance of imperialist foreign legions (for instance Opération Barkhane in the Sahel) is yet another sign of the self-reproducing nature of the contradiction. Anyone who disregards the wrongs done to Muslim populations by European (and US) imperialism at home and abroad and considers the struggle waged by organisations such as Al Qaeda and ISIS as historical anomalies that have come from nowhere is simply at a loss to understand, and hence to solve, the problem at hand. These are barbaric organisations that should be understood in order to be cleverly fought against, just as, in a wholly different context, one has to understand the nature of fascism in order to defeat it.

The comeback of the third wave of world revolution

We have so far played the Cassandra purposefully for to ignore the dire and multifaceted dangers to the future of humanity prepared by capitalism would be folly. And yet we think the panacea also offers itself in very real terms. This is what we call the third wave of world revolution.

The first and second waves of world revolution in the modern capitalist age came about respectively after the Great October Revolution and World War II. There is no reason why we should take the trouble of explaining to the reader why these were waves of world revolution as everything points to the international nature of these two waves of revolution, irrespective of whether each and every revolution within those waves ended in victory.

The Third Great Depression gave rise to the first revolutions of the 21st century in the Arab world. Tunisia and Egypt were the pioneers, but the revolution had its impact on all Arab countries (with the notable impact of Libya, which was a tribal and regional war that ended in a reactionary turn of events). The Arab revolution of 2011-2013 became a source of inspiration to the rest of the world. The Mediterranean basin saw a plethora of popular rebellions in this period. Mass mobilisation even jumped across the ocean to the US (“Occupy Wall Street”) and Brazil. Thus, in our opinion, a new wave of revolutionary mobilisations, whether victorious or defeated or abortive revolutions or popular rebellions with no claim on gaining political power, was born, which we called in 2013 the third wave of world revolution in the capitalist era.

The defeat of the Egyptian revolution, which was the pivotal experience of that period, along with other factors, brought a lull to the revolutionary activity of the masses not only in the Arab countries but around the world as well. We pointed out that this was temporary and that the masses, having been defeated and pushed back on the field of uprisings, were now forcing parliamentary channels. Witness the examples of Bernie Sanders in the US, Jeremy Corbyn in the UK, Syriza in Greece, Podemos in Spain, or, somewhat later, the victory of Andrés Manuel López Obrador in Mexico. We did not for one moment believe that any serious good would come out of these experiences, but took them as indicators of the fighting mood of the masses.

At the end of 2018, we wrote a two-part article, stressing that 2018 was the year of “inflection” since 12 popular rebellions had erupted in 12 different countries in the space of that year, of which the prime example was probably the Yellow Vests movement in France (see in particular http://redmed.org/article/2018-year-resurgence-third-wave-world-revolution). “Inflection” has now turned, in 2019, into a fully-fledged explosion of uprisings, popular rebellions and revolutions of an unseen variety and degree. The leader is again the Arab world, with Sudan, Algeria, Iraq and Lebanon each experiencing a revolution this year. However, the Latins, as ever, have not been long to catch up: Haiti, Puerto Rico, Ecuador, Chile, and Columbia all went through periods of convulsion. The Bolivian popular masses responded to the coup that brought down Evo Morales with an outburst of revolutionary energy. Their central slogan was “ahora sí, guerra civil” (“yes then, civil war”), throwing the gauntlet onto the face of the coup-mongers hypocritically acting as teachers of morality.

Another country in the Middle East, non-Arab this one, has been on the move since the last days of 2017-early 2018. In these two years, Iranian masses attempted to occupy the streets of the country several times, but failed to do so under heavy repression. They also engaged in strike actions, women’s protests, a teachers’ movement etc. The last attempt at gaining control of the cities was of a ferocity that can rarely be seen even in revolutions (see our http://redmed.org/article/burn-all-banks-iranian-brothers-and-sisters-until). It lasted less than a week, but was again repressed under the iron hand of the mullahs’ regime, leaving behind hundreds of dead, figures quoted reaching all the way to 1,500. The demonstrators burnt scores or even hundreds of bank branches and attacked the Central Bank headquarters, as well as symbols of the religious administration of the country.

France was once again the shining light on the continent of Europe. Against Macron’s attack on pension rights, a rolling strike was started that paralysed the country, with three days of action that gathered crowds across the country that varied between one million and 1.8 million. Even with Christmas arriving refineries were going into high gear. There were mobilisations in other countries as well, from Zimbabwe in Africa to Indonesia in south east Asia.

There are some commonalities in these revolutions and popular rebellions. First, most if not all have been triggered by economic factors and are, therefore, of a class nature. Elimination of subsidies to oil products, a rise in bread or transportation prices, an attack on acquired economic rights, high unemployment, a lack of very basic social services such as electricity or running water are all excuses for a powerful rise of the masses, at times directly resulting in revolutions.

Secondly, in most cases these mobilisations will not stop short of changing the structure of power, bringing around a new regime and holding all earlier cadres in power accountable. Whatever concessions of an economic, political or legal nature are made, the crowds will not budge an inch unless “they all go”, “killon yani killon” as the Lebanese revolution expresses it. Many heads have rolled, prime ministers and governments have been brought down, but the thirst of the masses has not been quenched.

Thirdly, despite the clear class-economic basis of these mobilisations, more well-to-do sections of the population also participate in these uprisings, partly for their own economic reasons (high rates of graduate unemployment, low pay, corruption and nepotism, miserable social services etc.), but partly also for cultural or non-class-based forms of oppression. This tends to create frictions at times and tactical and strategic differences at others between these layers of the modern petty-bourgeoisie (the liberal professions etc.) and the upper layers of a semi-proletariat (company cadres and state officials, upper echelons of the employees of the culture industries etc.)., on the one hand, and the proletarian and plebeian elements.

Fourthly, although fighting the forces of repression heroically, the masses are afflicted with a very low level of political consciousness. This is due to the great defeat suffered by socialist ideas as a result of the collapse of the experiences of socialist construction at the end of the 20th century.

The fundamental contradiction that besets these revolutions and popular rebellions, though, is the rise of revolutionary masses in search of political power without any revolutionary political party that has been formed and prepared to lead them to power. It is this aspect that is decisive because in the absence of such parties all the foregoing problems (and others that we have not mentioned for lack of space) which beset the revolutions at hand become unresolvable. So the nodal point that has to be grasped is this absence of revolutionary parties. The immediate duty is to create such parties so that future revolutionary leaps are not left dangling in the air as the ones today mostly are condemned to remain.

Conclusion

It is clear from all that has been said above that humanity is standing at the crossroads of a choice between a future in which repressive and exploitative forces try to overcome the difficulties capitalism is facing in the most reactionary manner and another in which all exploitation and violence will be brought to an end and humanity can live in a classless society in a borderless world.

The period in which we are living is, in a certain sense, much more difficult than the first two waves of the world revolution, which coincided, as the third also does, with great crises caused by capitalism. It is much more difficult because, as opposed to the two previous experiences, this time around there are no parties almost anywhere which are rooted within the ranks of the mass of the people and which can lead them to revolutionary victory. To fill this void is the burning task of our day and age, not only building revolutionary parties in each and every country, but also a revolutionary International.

In another respect, though, we are luckier. Revolutions came at the end of both world wars in the 20th century, after a loss between 10 to 20 million in 1914-1918 and upwards of 60 million during World War II. This time, revolutions have come early, without fascism having got hold of a stronghold or before the outbreak of a world war. Let us then make ample use of the benefit of this early response of the masses to the crisis, organise the masses and their vanguard party so as to bring down this vile order that secretes such reactionary phenomena.